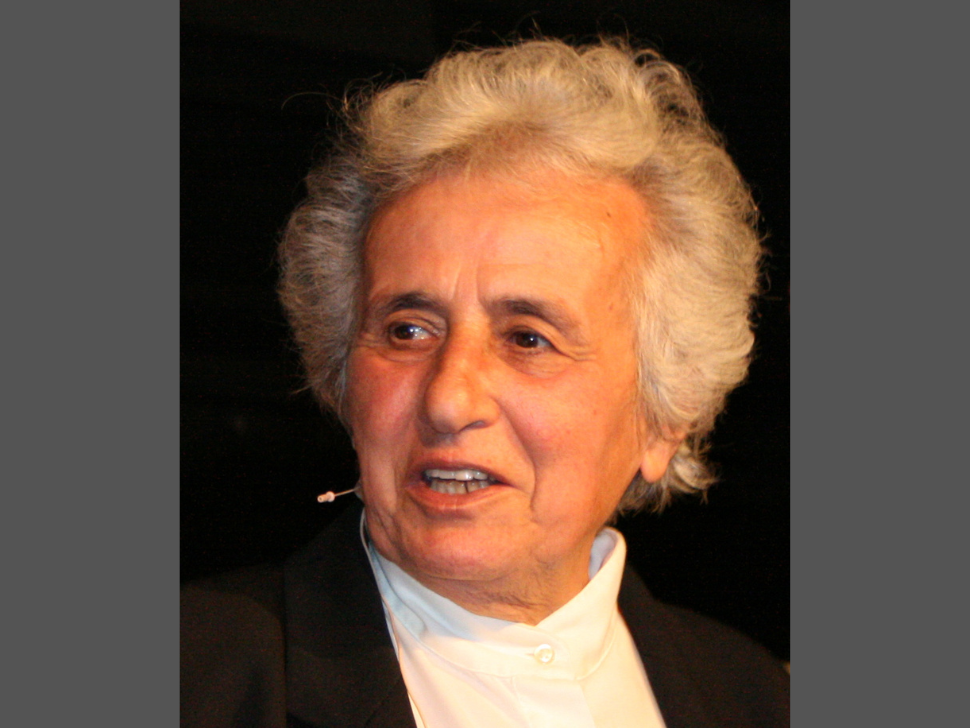

“The Cello Saved My Life”: Anita Lasker-Wallfisch Marks 100 Years as One of the Last Witnesses of Auschwitz

Holocaust survivor, cellist, and tireless advocate for remembrance, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch turned 100 on July 17, 2025. Her extraordinary life, shaped by unimaginable tragedy and resilient hope, has made her one of the most powerful living voices of Holocaust testimony. But as she celebrates her centenary, Lasker-Wallfisch is also sounding a somber warning: the lessons of the past are fading in a world where antisemitism is again on the rise.

A Life Saved by Music

Born in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) in 1925, Anita Lasker grew up in a cultured, assimilated German-Jewish family. Her father was a lawyer and war veteran, her mother a violinist. Though not religious, the family became targets of Nazi persecution after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933.

Lasker-Wallfisch was just a teenager when her parents were deported and murdered in 1942. She and her sister Renate, both working as forced labourers in a paper factory, were arrested for forging documents to help French prisoners escape. In December 1943, Anita was sent to Auschwitz. Her life was spared only because she could play the cello.

She joined the Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz—a group of female prisoners forced to perform for camp operations and SS officers. “The cello saved my life,” she would later reflect. “Not a single one of us believed we'd make it out of Auschwitz in any other way than up the chimney.”

In late 1944, as the Soviet army approached, she was transferred to Bergen-Belsen. There, unlike in Auschwitz, people weren’t systematically murdered—they simply died from starvation, disease, and neglect.

When British troops liberated Belsen in April 1945, Lasker-Wallfisch was among the few left alive. The very next day, she delivered a report to the BBC’s German service, pleading: “The Auschwitz prisoners, the few that remain, all fear the world will not believe what happened there.”

Bearing Witness

In the postwar years, Anita emigrated to Britain, married pianist Peter Wallfisch, and became a founding member of the English Chamber Orchestra. But for decades, she remained largely silent about her past—even to her children. Her daughter Maya once asked about the number tattooed on her mother’s arm. The answer? “I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

Eventually, she found her voice again. Her 1996 memoir Inherit the Truth made her internationally known. She travelled to German and Austrian schools to educate the next generation, believing survivors had a duty to speak for the millions who were silenced. “I’ve spoken with thousands of schoolchildren. If just 10 of them behave properly, I’d be satisfied,” she once said.

In 2018, she delivered a powerful speech before Germany’s Bundestag on Holocaust Remembrance Day, condemning growing complacency and warning against “drawing a line under” the past.

She also participated in “Dimensions in Testimony,” a digital project that allows people to interact with recorded holograms of Holocaust survivors. Even after her death, she wanted her voice to remain.

“She’s in Despair”

Despite a life of activism, Lasker-Wallfisch is deeply disheartened by today’s climate. Her daughter Maya told Jüdische Allgemeine Zeitung that Anita is “in despair,” feeling that her decades of effort have not stemmed the tide of hate.

There are troubling signs to support her unease. A recent Jewish Claims Conference survey found that 12% of young Germans have never heard of the Holocaust. Since the war in Gaza, global antisemitism has spiked dramatically.

“Is it important whether you’re Jewish?” she told Süddeutsche Zeitung. “You’re simply a human being.”

A Milestone Marked in Music

Despite the bleak outlook, friends, family, and admirers are gathering to celebrate Lasker-Wallfisch’s remarkable 100 years. A concert in her honour was held at London’s Wigmore Hall, attended by international dignitaries, her two children—cellist Raphael Wallfisch and psychotherapist Maya Jacobs-Wallfisch—and generations of descendants.

Even King Charles III visited her home in north London in the lead-up to her birthday.

Lasker-Wallfisch recently appeared in the documentary The Commandant’s Shadow, where she met Jürgen Höss, the son of Auschwitz camp commandant Rudolf Höss. The film explores the weight of legacy, trauma, and reconciliation through their encounter.

“We Still Think We’re Dreaming”

In her first words to the BBC in April 1945, Anita said, “We still think we’re dreaming.” That sense of disbelief lingers—though now it’s less about liberation and more about how the world, once again, seems to be forgetting.

As Lasker-Wallfisch celebrates a century of life, what she wants most is not recognition, but resolve: for the world to remember, and for the poison of antisemitism to be rooted out once and for all.

It’s a wish she knows may not be fulfilled in her lifetime—but it’s one she has never stopped fighting for.

For those who want to learn more about the Holocaust, the Freeman Family Foundation Holocaust Education Centre at 123 Doncaster Street offers a powerful and immersive experience. Located within the Marion and Ed Vickar Jewish Museum, the Centre invites visitors to enter through replica boxcar doors—an evocative reminder of the countless lives transported to death camps during the Shoah. Inside, permanent exhibits featuring photographs, original documents, and artifacts donated by Manitoba survivors bring the history to life. With space for groups of 10 to 50, the Centre is equipped for presentations and regularly welcomes students, interfaith groups, service clubs and others. A reading room with Holocaust literature and internet access is available for research, and a Kaddish corner offers a space for prayer and reflection. To arrange a tour or book a presentation, visitors are encouraged to contact the office directly.