David Korevaar’s Beethoven Journey: A Monumental Cycle with Heart, Intellect—and a Bit of Mozart

A pandemic project reborn

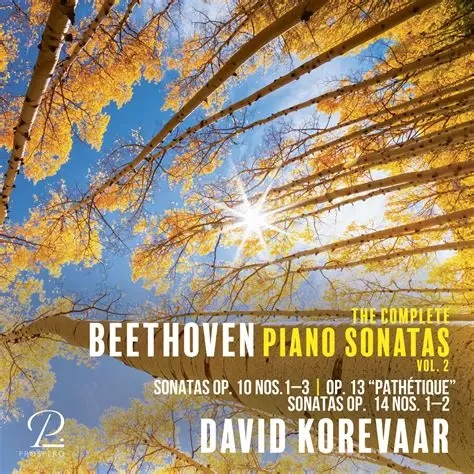

In March of this year, pianist David Korevaar launched an ambitious new recording project with Prospero Classical: a six-volume cycle of all 32 Beethoven piano sonatas. Rolling out over the summer and into the fall, the series brings new life to these revolutionary works through Korevaar’s seasoned artistry and personal insight.

But as Korevaar explained, this wasn’t his first encounter with the full cycle.

“During the pandemic, I did what a lot of us did and produced bad videos from my home because that’s all we could do,” he recalled. “And of course, the piano tuners wouldn’t come to our homes either. So not only is it bad video and bad audio, but it’s also out of tune.”

Though those performances garnered a wide online audience, Korevaar saw the Prospero project as an opportunity to do justice to the music with high production values and first-rate sonics. “This is my opportunity to do it right… to put it out really for a broader audience,” he said.

Studying with Earl Wild: “You don’t know anything when you’re a kid”

A Juilliard-trained pianist and current faculty member at the University of Colorado, Korevaar is no stranger to the great traditions of pianism. He studied with the legendary Earl Wild for many years—though he says the lessons took time to sink in.

“I was a kid. And when you're a kid, you don't know anything,” Korevaar said with a laugh. “I think it took me another eight years after studying with him for eight years to actually figure out what he told me.”

He remembers Wild’s singular technique and sound with admiration. “Anytime I listen to one of his recordings again, I'm just kind of blown away actually by what he could do,” he said, adding that Wild was often unfairly pigeonholed as a “cheap virtuoso.” In Korevaar’s view, recordings like Wild’s Brahms Ballades or the F minor Sonata show a depth of musicianship that defies the stereotype.

Choosing the ‘splashy’ sonatas first

Volume 1 of the series features two discs: one with the sonatas Nos. 21–23—Waldstein, Op. 54, and Appassionata—and a second with Nos. 28 and 29, including the towering Hammerklavier.

Although the rest of the series will follow a chronological path, Korevaar chose to lead with this “splashy” trio of middle-period works. “Everybody likes the ones that have names,” he joked, “even if the names don't have anything to do with the content of the work or weren't given by Beethoven.”

But there was deeper reasoning, too. “To me, what's happening here is what always happens in Beethoven. This is a great representation—he’s searching for a new style,” he explained. He believes Waldstein in particular was influenced by a production of Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio, citing musical quotations and allusions to alla turca style embedded in the piece.

The personal Beethoven

For Korevaar, Beethoven’s piano sonatas are intensely personal. “Regardless of the reason he wrote the piece, it was something very personal for him. It was his sandbox. It was his opportunity to try things.”

This spirit of experimentation is evident in the lesser-known Sonata No. 22, Op. 54. “It’s a real oddity,” he said. “Structurally, he's in a very strange place… The level of contrast that he arrives at is something really unprecedented.” The second movement, he noted, is perpetual motion—"one of the harder ones to play"—written entirely in two-part counterpoint.

Beethoven and the evolving piano

The increasing technical demands of Beethoven’s piano writing coincided with innovations in the instrument itself. Korevaar highlighted Beethoven’s French-built Érard piano, which extended the keyboard’s range and gave him new creative possibilities. “He clearly was always frustrated with the range of the instrument,” he said. “This is a kind of liberation.”

That expansion of range and dynamic power allowed Beethoven to create the emotional extremes that characterize so many of the sonatas—especially in Appassionata. “At the very beginning… he moves from pianissimo to fortissimo. It’s just such a shocker,” said Korevaar. “It’s one of the largest contrasts we have in a Beethoven sonata.”

The German identity of late Beethoven

The second disc in Volume 1 features Sonatas Nos. 28 and 29, composed as Beethoven leaned into a strong sense of German cultural identity.

“In early works, he's always ‘Louis van Beethoven,’” Korevaar noted, pointing to the use of French on title pages and Italian tempo markings. But by Op. 101, Beethoven was deliberately choosing German terms, such as Langsam und sehnsuchtsvoll—“slow and full of longing.”

“He’s after subtlety,” Korevaar said. “He’s after depth in the marks.” Though the pieces began with Italian markings, the German was often added later—an “ex post facto Germanization,” as Korevaar put it.

The Hammerklavier: “It is intimidating, but wonderful”

No. 29, the Hammerklavier, is a Mount Everest of the piano repertoire. “I think Beethoven wanted us to be daunted by it,” Korevaar said. “It’s one of the most heartfelt, heart-rending, beautiful, and compositionally fascinating things anybody has ever written.”

Despite its technical ferocity, Korevaar emphasized the work’s emotional centre: the immense slow movement. “I can’t ever quite believe how wonderful it is,” he said. “That movement alone is a universe.”

He takes issue with Beethoven’s infamous metronome markings for the sonata, which many scholars deem unplayable. “If you really play them at that speed, the music is completely garbled,” Korevaar said. “It makes much more sense to play the pieces as music than to worry about achieving this kind of unachievable speed.”

Both Sonata No. 28 and Hammerklavier feature dazzling fugal writing. Korevaar finds the fugue in No. 28 especially awkward to play: “You have to use your hands in a way that is so unconventional… It’s harmonically very unconventional, too.”

In the Hammerklavier, Beethoven pushes even further. “These quick fugues… are really daunting because you’ve got to keep all these balls in the air. And none of these balls have terribly predictable flight patterns.”

A rediscovery of joy and depth

For Korevaar, the most rewarding part of this journey has been revisiting the earlier sonatas. “Going back… to some of the earlier sonatas, some of which I’ve known for 40 years or more… just seeing again, like in Opus 10 No. 3 or Opus 22… what a phenomenal gift Beethoven had.”

“It is intimidating,” he said. “But at the same time it’s wonderful… This is a human being who created so much great music and with such consummate skill—but always with his heart.”

If you think you know Beethoven’s piano sonatas, think again. Volume One of David Korevaar’s new cycle on Prospero Classical kicks things off with a riveting combination of power, poetry, and precision. Featuring the fiery Appassionata, the majestic Waldstein, and the quirky, often-overlooked Op. 54, this release captures Beethoven at a moment of bold experimentation and expressive depth. Korevaar brings these middle-period works vividly to life, balancing emotional intensity with architectural clarity. With top-tier production and interpretive insight, this first volume is a thrilling start—and if it's any indication, the rest of the cycle promises to be just as engaging, illuminating, and enthralling.

The Beethoven Piano Sonatas by David Korevaar – Volume 1

Available now via Prospero Classical on all major digital platforms. More volumes to be released throughout the summer and fall, with a grand reissue of the complete set planned for January.