A Taste of Manitoba: When Composers Meet Cuisine

As A Taste of Manitoba gears up to ignite Fort Gibraltar with local flavours, it’s only fitting to cast our minds back to how the world’s greatest composers fueled their creativity—through highly personal, often eccentric diets. Exploring Ludwig van Beethoven’s bean-counting coffee ritual or Erik Satie’s devotion to white foods isn’t just fun trivia—it’s a reminder that eating has always been a deeply creative act. This unique lens underscores the nuancing of taste, much like the varied culinary delights of the festival itself.

-

A Taste of Manitoba runs from August 28 to September 1, 2025, hosted at the historic Fort Gibraltar in Winnipeg’s St. Boniface neighbourhood.

-

The festival features around 20 local restaurants, each offering signature sampler dishes that showcase the province’s culinary diversity

-

Produced by the Manitoba Restaurant & Foodservices Association in partnership with Fort Catering, the event revives a beloved local tradition, offering food, drink, chef demos, family games, music, and more in a free-entry, ticket-for-tasting format

Ludwig van Beethoven – The bean counter of Bonn

![]()

Beethoven approached his diet with the same obsessive attention he gave to music. His day famously began with coffee — but not just any coffee. He personally counted exactly 60 beans for every cup, grinding them by hand to achieve the “perfect” brew. His friends described him as fiercely particular, never allowing servants to prepare it. Beyond coffee, Beethoven’s meals were modest: he favoured fish, eggs, and vegetables, with macaroni and cheese often on the menu. He wasn’t one for elaborate dining; instead, his food choices reflected a man consumed by routine and discipline. One could argue his music was fuelled as much by beans as by inspiration.

Richard Wagner – The radical vegetarian

![]()

Wagner’s passion for philosophy extended to the dinner table. He was heavily influenced by the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer and believed a meatless diet elevated the spirit. For long stretches of his life, he lived almost entirely on fruits, vegetables, and coarse brown bread. His wife, Cosima, often wrote in her diaries about the composer’s soups and stews made from lentils, beans, and potatoes. Wagner’s devotion to vegetarianism was unusual for the 19th century, and he linked it directly to artistic purity, claiming heavy foods dulled creativity. His operas may be grand and indulgent, but his diet was rooted in restraint and ideology.

Gioachino Rossini – The gourmet maestro

![]()

No composer embodied culinary excess like Rossini. Nicknamed “The Swan of Pesaro,” he quit composing at just 37, reportedly saying he had written enough operas — and now wanted to eat. He became a passionate gourmand, devoting himself to rich French cuisine. Foie gras, champagne, and truffles were his trinity. In fact, he was so enamoured of truffles that dishes such as Tournedos Rossini (steak topped with foie gras and truffle) were created in his honour. Rossini even dabbled in recipe writing himself. He once quipped: “I have wept only three times in my life: when my first opera failed, when I first heard Paganini play, and when a truffled turkey fell into the water.” Food was his second art form, and indulgence his favourite key signature.

Franz Liszt – From paprika to piety

![]()

Liszt’s diet reflected the two halves of his remarkable life. In his youth, the Hungarian virtuoso was the very definition of excess. He enjoyed hearty Hungarian dishes like paprika-laden goulash, fine wines, and sumptuous banquets thrown in his honour. But as he aged, Liszt underwent a profound transformation. Turning toward spirituality and a semi-monastic lifestyle, he abandoned meat and adopted a vegetarian diet. His meals became starkly simple: bread, fruit, and milk, often consumed in solitude. Visitors noted how little he cared for the pleasures of the table in his later years, focusing instead on contemplation. His diet traced his evolution from flamboyant showman to ascetic sage.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – The playful gourmand

![]()

Mozart’s letters reveal a man who adored hearty, homely food. He was especially fond of liver dumplings and sauerkraut, and he washed them down with plenty of beer. His appetite for sweets was legendary: marzipan, strudel, and candied fruits were among his indulgences. Unlike Beethoven’s rigid routine or Wagner’s philosophy-driven diet, Mozart’s approach to food was carefree, playful, and deeply social. He often wrote jokes about meals to family members, and dining out was one of his simple joys. Food was another outlet for his humour and energy — exuberant, abundant, and always a little mischievous, just like his music.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – The anxious ascetic

![]()

Tchaikovsky’s relationship with food was marked by his fragile health and anxious temperament. Convinced that rich or heavy meals would worsen his ailments, he kept to a restrained, almost clinical diet. Light soups, fish, porridge, and tea dominated his table. He often wrote in his diaries about fears of indigestion or illness, reflecting how his nerves shaped his eating habits. Wine was sometimes taken in moderation, but excess of any kind was avoided. His diet may seem austere compared to Rossini’s feasts, but it suited a man constantly on guard against emotional and physical collapse. His reserved appetite was the quiet counterpoint to the stormy emotions in his symphonies.

Johann Sebastian Bach – Brewing inspiration

![]()

Bach’s table was not without indulgence. Living in Leipzig, he enjoyed a steady supply of beer, which was a staple in German households of the time. He wasn’t shy about his fondness for it, often drinking several mugs in a day. Coffee was another obsession: his Coffee Cantata pokes fun at society’s caffeine craze but also highlights his own love of the drink. Meals in the Bach household were robust — bread, meats, and hearty fare — feeding not only himself but a sprawling family of 20 children. Unlike the ascetic Liszt or the anxious Tchaikovsky, Bach embraced food and drink as a joyful part of daily life, much like his buoyant fugues and chorales.

Claude Debussy – The refined palate

![]()

Debussy’s Parisian sensibilities extended into his cuisine. He adored oysters and seafood, often paired with good white wine. His tastes leaned toward the refined and delicate, mirroring his musical aesthetic. He wasn’t an over-indulger but sought balance and nuance in his meals. Debussy’s dining habits reflected a man who valued atmosphere: conversation, a fine glass of wine, and a subtle dish of fish or shellfish. Food, for him, was an art of suggestion — much like his music, which hinted and shimmered rather than shouted. His plate, like his scores, was a study in subtlety.

Igor Stravinsky – Order and restraint

![]()

Stravinsky carried discipline from his composing desk to his dining table. He favoured light, carefully portioned meals — eggs, fruit, salads, and lean meats. He disliked extravagance and avoided overindulgence, believing order in eating encouraged order in thought. He was also particular about timing: meals had to fit neatly into his strict working schedule. Even in later life, when fame and fortune afforded him any luxury, Stravinsky remained spartan in his tastes. His diet mirrored his approach to music: precise, exacting, and stripped of excess, but brimming with energy beneath the surface.

Erik Satie – The white-food eccentric

![]()

If there was a prize for strangest diet, Satie would win it. The French eccentric declared that he ate only white foods. His menu included eggs, rice, coconut, turnips, bread, sugar, milk, and even the odd mention of “shredded bones” and “animal fat.” He drank only white wine and water. Satie’s obsession with monochromatic eating was part of his overall odd persona: he owned dozens of identical grey suits, carried a hammer for no apparent reason, and lived in near poverty. His bizarre dietary rules aligned with his radical minimalism in music, where repetition and stark simplicity shocked audiences. For Satie, meals were performance art — strange, severe, and unforgettable.

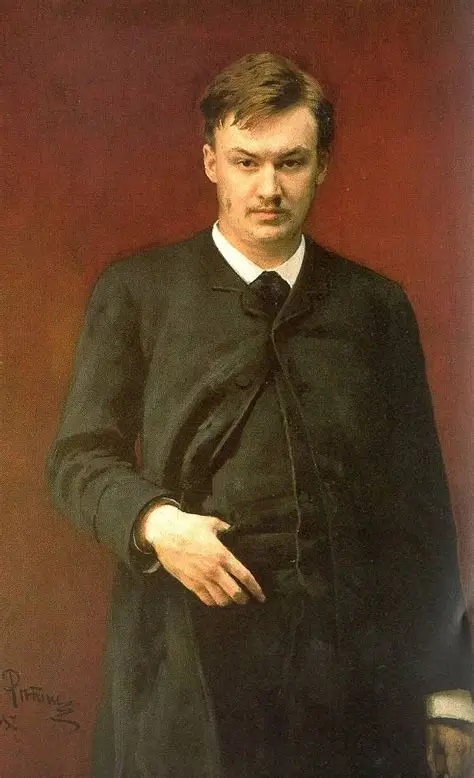

Alexander Glazunov & Jean Sibelius – Symphonies in a glass

Not all composers fuelled their creativity with food — some found their muse in the bottle. Alexander Glazunov was notorious for his prodigious drinking; colleagues recalled him conducting entire concerts with a flask hidden in his coat, keeping the orchestra together while barely keeping himself upright. His dependence on alcohol shadowed his otherwise prodigious gifts as a teacher and composer. Jean Sibelius, meanwhile, paired his love of the Finnish landscape with a lifelong romance with strong drink, particularly champagne and gin. Though his drinking binges often stalled his productivity, he insisted that alcohol heightened his imagination and helped him access a deeper, freer form of inspiration. For both men, the glass was as much a part of their artistic process as the pen or the piano.

From Rossini’s truffle-stuffed feasts to Satie’s monochrome meals, composers’ diets remind us that food has always inspired creativity, indulgence, and ritual. Just as these maestros found joy, discipline, or eccentricity in their meals, A Taste of Manitoba invites attendees to celebrate the artistry of flavour across the province. Running August 28 to September 1, 2025, at Fort Gibraltar in Winnipeg, the festival features around 20 local restaurants, offering signature sampler dishes, live music, chef demonstrations, and family-friendly activities. Guests can expect a vibrant atmosphere, the chance to taste a wide variety of culinary creations, and a festive experience that proves good food, like great music, has the power to bring people together.