‘Violin of Hope’ crafted in Dachau hides message from imprisoned luthier

In the shadows of history’s darkest chapter, a message of hope has emerged from the most unexpected of places: the inside of a violin built in the Dachau concentration camp during World War II.

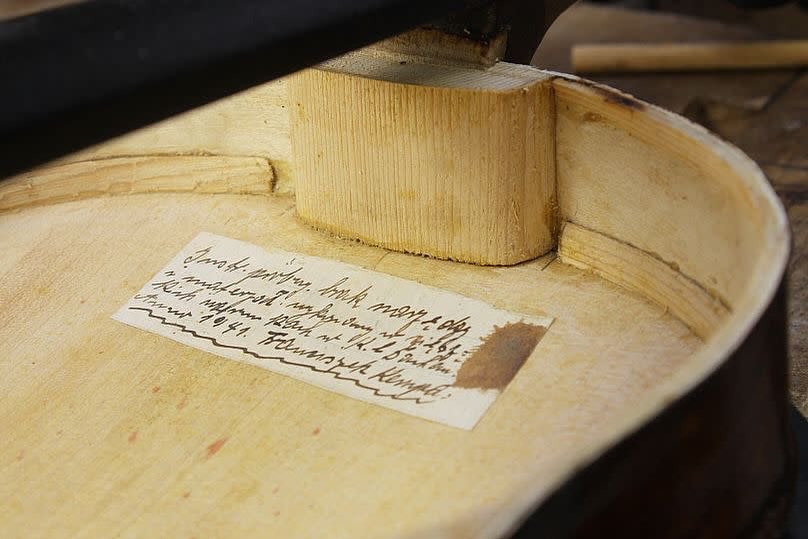

Crafted under unimaginable conditions in 1941, the violin was the work of Franciszek “Franz” Kempa, a Polish Jewish prisoner and master luthier imprisoned at Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp established near Munich. Hidden within the instrument for over eight decades was a handwritten note that simply reads: “Experimental instrument, made under difficult conditions without tools and materials. Dachau. Year 1941, Franciszek Kempa.”

The violin’s extraordinary story only recently came to light when Hungarian art dealers Szandra Katona and Tamás Tálosi sent it for repairs. They had found it stored among furniture they had purchased, intending to donate it. Though initially unaware of its origins, they were struck by an odd contradiction—the violin was crafted with great skill but made from poor-quality materials. “If you look at the proportions and the structure, you can see that it is the work of an experienced craftsman,” said Katona. “But the choice of wood was completely incomprehensible.”

That mystery led a professional restorer to open up the violin—revealing Kempa’s hidden message, written in a Silesian dialect that blends Polish and German. What they found was more than a note; it was a silent cry from a prisoner, an apology for compromised craftsmanship, and a testament to the enduring power of purpose in the face of dehumanizing brutality.

Photo Credit Boko Suzuki/ Facebook

While musical instruments were not uncommon in Nazi camps—often used by the regime for propaganda and to mask the horrors within—Kempa’s violin is believed to be the only known instrument constructed entirely within a concentration camp. All others are thought to have been brought in by prisoners.

Kempa, born in 1903, somehow survived the war. According to documents from the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, he returned to Poland after liberation in 1945 and continued making instruments until his death in 1953. The records also confirm that the Nazis were aware of his skills as a luthier—an expertise that may well have saved his life.

Tálosi and Katona have since dubbed the instrument the “Violin of Hope.” For them, it symbolizes more than just survival; it speaks to the resilience of the human spirit. “When you have a project or a challenge in front of you, you can overcome even the most extreme situations,” said Tálosi. “You focus not on the problem, but on the task itself—and I think this helped the maker of this instrument to survive the concentration camp.”

How the violin left Dachau and made its way to Hungary remains a mystery. But thanks to the chance discovery of a concealed note and the diligence of its finders, the voice of one prisoner has found its way to the present day—echoing resilience, resistance, and the unyielding strength of human dignity.