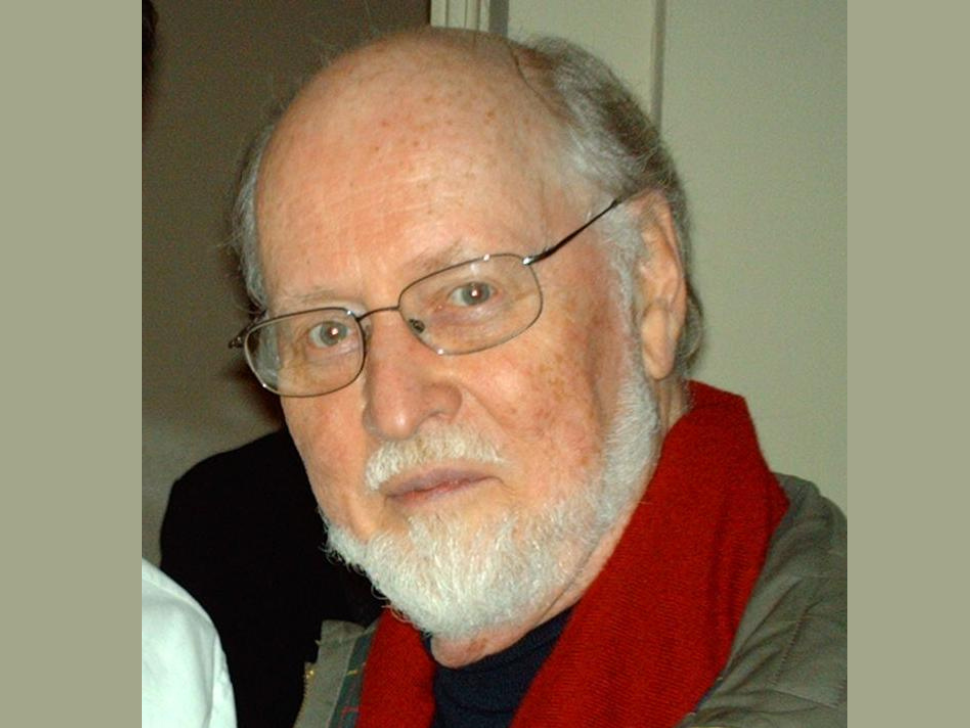

John Williams says he ‘never liked film music very much’ despite legendary career

John Williams may be the most decorated film composer alive, with more than 100 scores to his name and a record 54 Academy Award nominations, but the 93-year-old has revealed a surprising truth: he doesn’t think much of film music.

“I never liked film music very much,” Williams admitted in a rare interview for his forthcoming biography John Williams: A Composer’s Life, written by Tim Greiving and set for release this September by Oxford University Press.

While Williams has written some of cinema’s most iconic themes—from the menacing two-note shark motif in Jaws to the soaring heroics of Star Wars and the aching lament of Schindler’s List—he insists the genre doesn’t compare to the concert hall canon.

“Film music, however good it can be—and it usually isn’t, other than maybe an eight-minute stretch here and there … I just think the music isn’t there,” he said. “That, what we think of as this precious great film music is … we’re remembering it in some kind of nostalgic way. Just the idea that film music has the same place in the concert hall as the best music in the canon is a mistaken notion, I think.”

Williams went further, calling much of it “ephemeral” and “fragmentary,” only made whole when reconstructed for concert performance.

Greiving admitted he was startled by the composer’s dismissal. “His comments are sort of shocking, and they are not false modesty,” he told The Guardian. “He has this internalized prejudice against film music. It’s a functional type of music, which is funny because I consider his film music to be kind of sublime art at its best.”

Despite Williams’ modesty, his work is widely credited with redefining what film music could achieve, elevating it to high art. From E.T. and Indiana Jones to the first three Harry Potter films, his scores are inseparable from the emotional power of the movies themselves.

Still, Williams insists he treated film assignments pragmatically. “The film thing was a job to do, or an opportunity to accept,” he said. “If I had it all to do over again, I would have made a cleaner job of it—of having the film music and the concert music all being more me, whatever that is, or more unified in some way.”

Away from Hollywood, Williams has composed numerous concert works, including concertos for nearly every instrument in the orchestra, and served as music director of the Boston Pops for over a decade. His classical output has earned respect worldwide, even as his film music continues to dominate the cultural imagination.

Later this year, a new concert project titled John Williams Reimagined will present fresh arrangements of his most famous scores for flute, cello and piano at London’s Cadogan Hall on October 27, with an accompanying album release. Williams himself has endorsed the project, saying, “Pianist Simone Pedroni, flutist Sara Andon and cellist Cécilia Tsan have enhanced and elevated my music and that brings me great joy.”

Even if Williams downplays the significance of film scoring, generations of moviegoers and musicians would likely disagree. His music may not always live up to his own impossibly high standards, but it has undeniably shaped the way audiences hear—and feel—the movies.