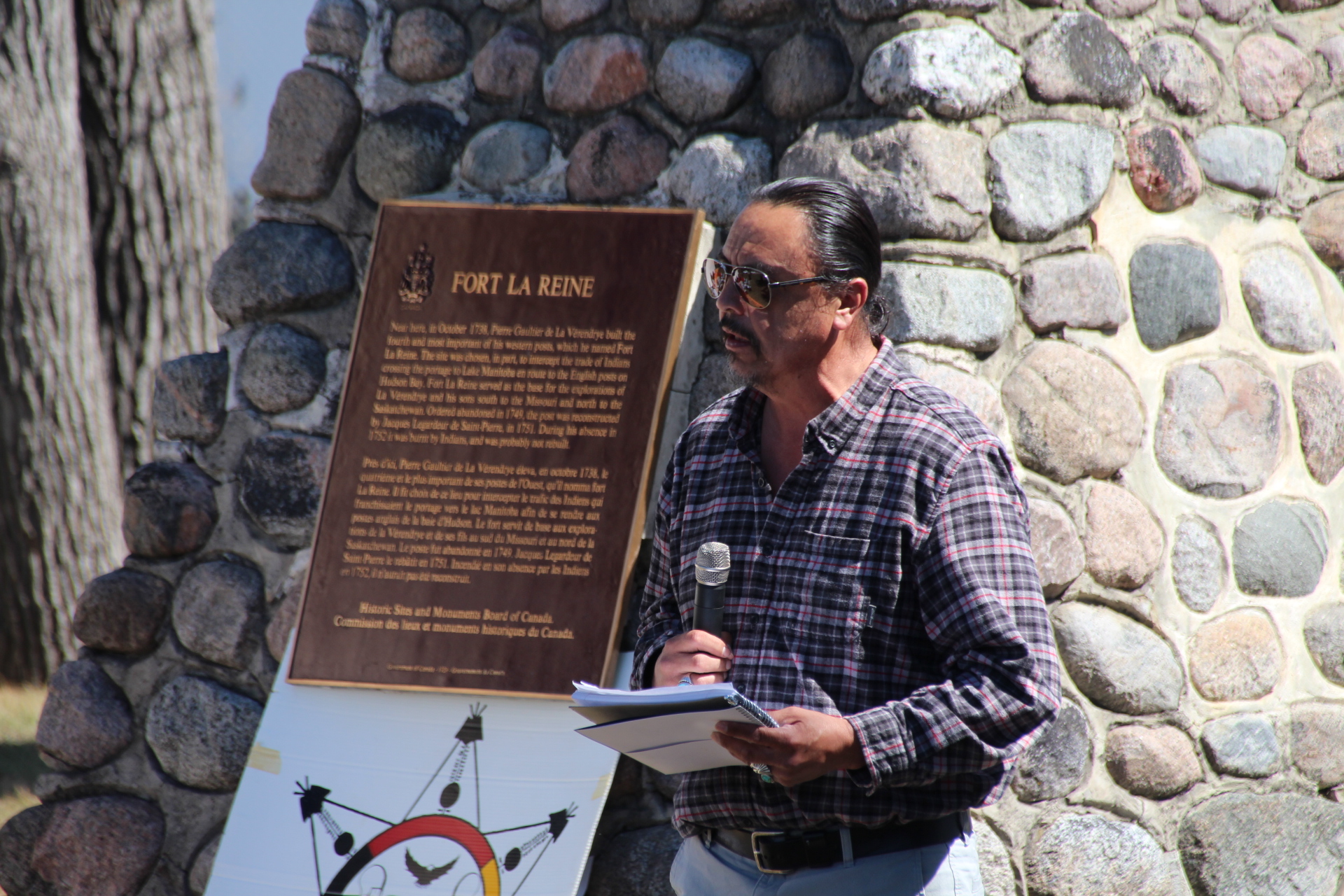

Dakota Tipi First Nation Chief Dennis Pashe was part of a gathering that marked a significant step in his First Nations' community’s land claims during a repatriation ceremony held this week at the Portage la Prairie Water Treatment Plant grounds. The site, located near the original "portage" where Fort la Reine was located on the Assiniboine River, symbolizes ancestral Dakota territory and ongoing efforts to affirm Indigenous sovereignty.

The Council of Manitoba Dakotas held the gathering, hosted by Dakota Tipi. Birdtail Sioux and Sioux Valley First Nations were present. Dakota treaties before the 1800s never get mentioned today, and the First Nations are seeking to spread this awareness.

Reconnecting with a 1700s French-Dakota agreement

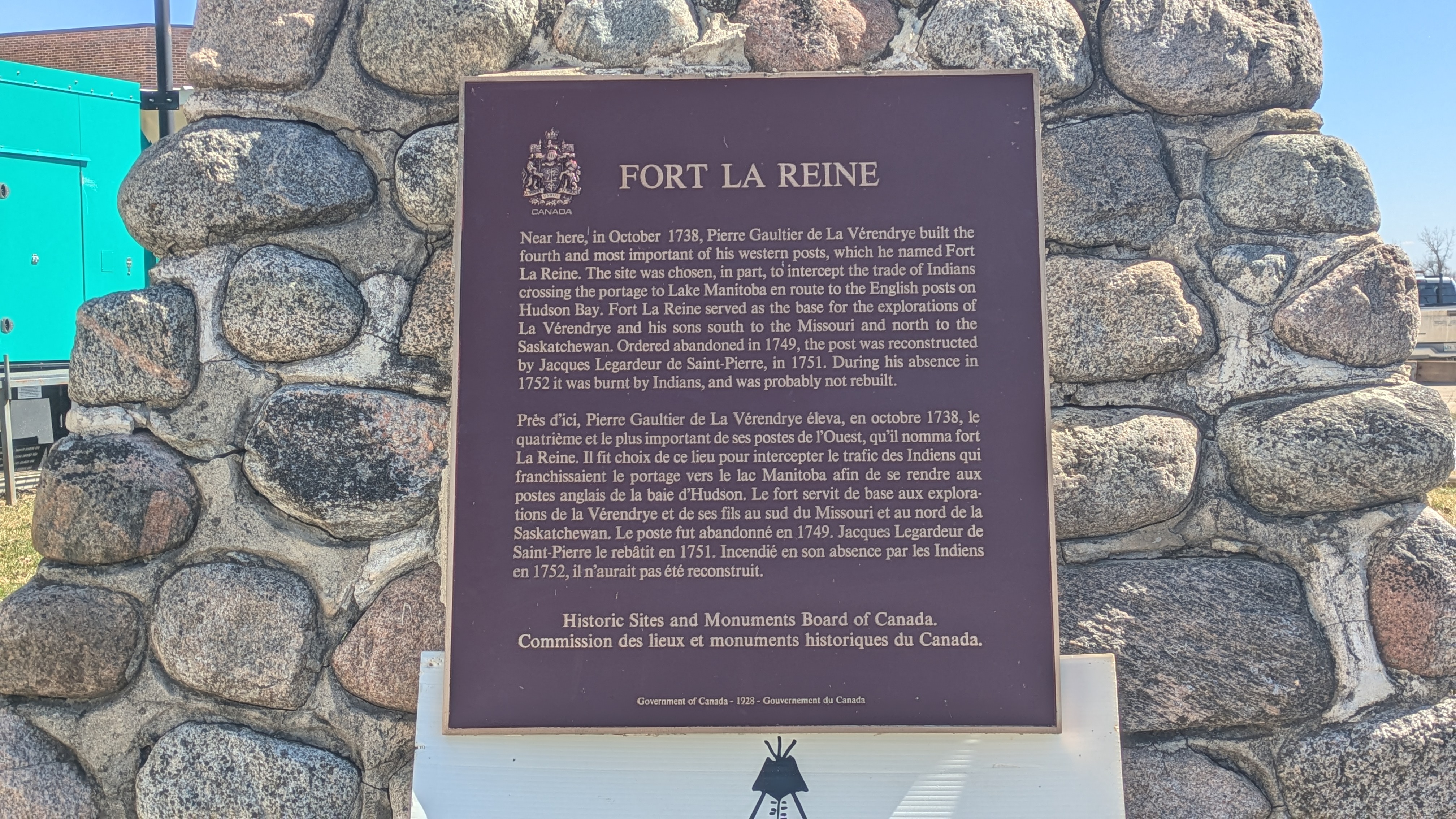

Pashe emphasizes that historical documents verify a treaty established between the Dakota and French explorer Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye in the 18th century, which he says forms the basis of modern land claims. “We have Aboriginal title to this territory,” he states, underscoring the First Nation’s legal arguments against Canada and Manitoba. The treaty, he adds, reflects “a series of reclamation of our territory and lands” supported by archival records.

The chief also stresses the need to protect burial sites scattered across the region. “Our people are buried in this territory, and so we need to be involved in any kind of developments to ensure their graves are not disturbed,” he continues. While the original treaty documents remain in French archives, Pashe acknowledges the challenge of accessing them but reaffirms their importance: “It’d be wonderful to get a copy of it for sure.”

“A fire of cooperation” amid colonization’s shadows

Geneva Smoke, lead researcher and archivist with the Dakota claims team, clarifies the treaty’s origins.

“We’re commemorating the 1738 Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Trade between the French and the Western Dakotas, signed at Fort Lorraine in Portage la Prairie. It was approved by the king. Today, we honour that agreement and teach our youth about its legacy.”

Smoke notes the treaty predates most Canadian Indigenous agreements but follows earlier pacts like an oft-overlooked 1650 accord between the Dakota and French explorer Pierre Radisson.

“This one was unique because it specifically involved the Western Dakotas, part of the Oceti Šakowiŋ Grand Council. Leaders from Sioux Valley, Dakota Tipi, Birdtail, and other communities are here to reaffirm its lessons.”

Smoke emphasizes the event’s focus on intergenerational education.

“We’re honouring La Vérendrye’s willingness to listen and learn rather than take. Treaties are living promises — not relics — guiding how we live today.”

She adds that archaeological evidence, like 12,000-year-old pottery fragments, reinforces Dakota ties to the land.

“Our ancestors’ archaeology proves their presence here long before colonization. What started as a personal hobby — researching my family’s history — became this collaborative work with researchers from Iowa to Alberta.”

Yet she does not shy from addressing the treaty’s fraught legacy.

“Those tides of history brought conflict, broken promises, and the shadow of colonization,” Smoke says. “But today, we gather to reclaim what was sacred in that moment: the recognition that our shared humanity is stronger than our differences.”

Organizers chose the October 3 ceremony to align with the treaty’s 1738 signing date. Smoke calls it a chance to “reclaim narratives erased by time” while building partnerships grounded in historical truth. Legal experts say the event could influence Indigenous sovereignty cases nationwide.

Pashe calls the ceremony a “historical day” in advancing Dakota claims, framing it as part of a broader journey.

“We have a lot of work ahead of us,” he says, “but we’re happy to move forward.”

Organizers say the ceremony reinforces calls for modern governments to honour historical agreements through substantive land stewardship partnerships. Legal experts anticipate the treaty could set precedents for Indigenous sovereignty cases nationwide.