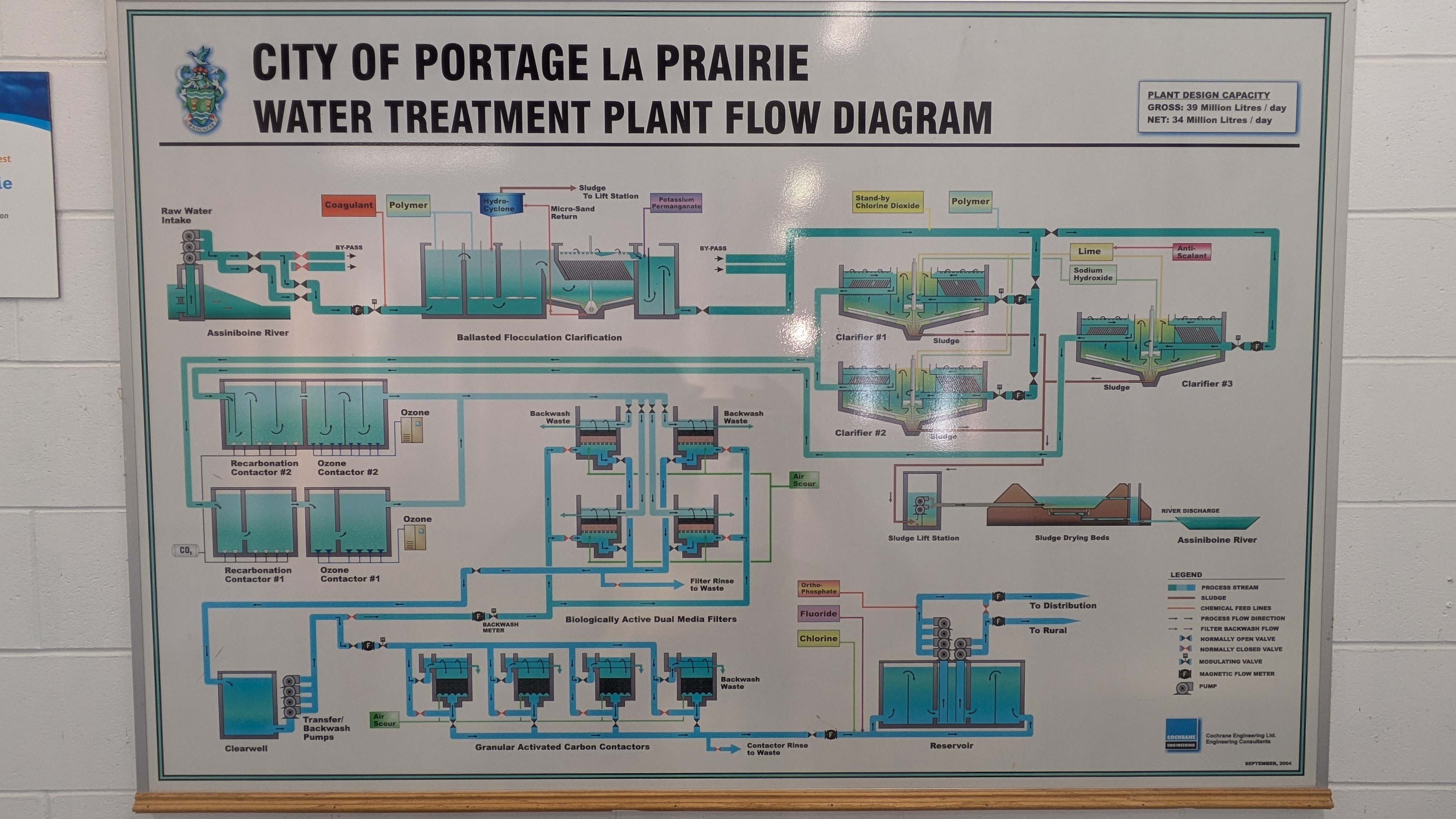

In the heart of the Portage la Prairie Water Treatment Plant, a complex network of pipes, clarifiers, filters, and chemical systems work together to convert highly turbid water from the Assiniboine River into award-winning drinking water.

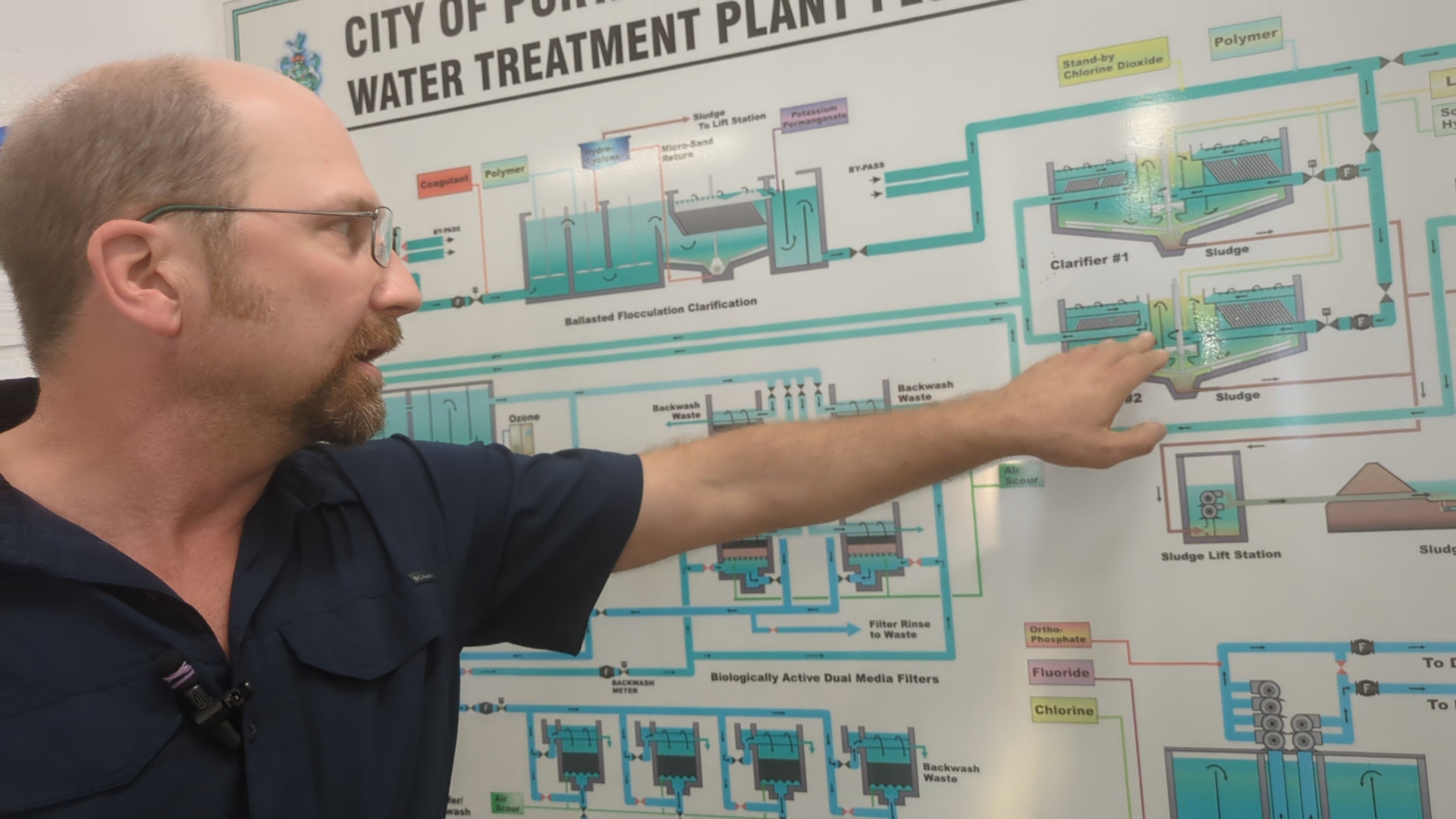

Jared Smith, Water Treatment Plant Manager for the City of Portage la Prairie, guides visitors through the facility, beginning in the quieter upper hallway, located near staff offices. Here, a detailed flow diagram outlines the plant’s multi-building system.

The raw water intake originates at the Portage Spillway Dam, built in 1971, which also supplied the city’s previous water plant. The current facility, constructed in 1978, is spread across three buildings in addition to the dam intake.

From the dam, three 125-horsepower pumps move raw water through dual pipelines to the western edge of the plant on Yellowquill Trail. This water then enters a pre-treatment facility housing a technology called active flow.

Active flow handles extreme turbidity

Smith explains that the active flow system uses micro-sand to accelerate the flocculation and clarification process. Polyaluminum chloride is added as a coagulant, followed by a polymer that causes fine particles to clump and sink.

“These particles attach to the micro-sand, which drops quickly in the clarifier section,” he says. “The clean water rises and flows into a chamber where we dose potassium permanganate during summer months for taste and odour.”

This entire process takes about 15 minutes, allowing for fast removal of suspended solids.

Smith notes that Portage la Prairie’s water requires more aggressive treatment than many other communities.

“Our turbidity levels from the Assiniboine River often exceed 2000 NTU in the spring,” he says. “That’s not just high — it’s chocolate milk dirty.”

Clarifiers take over after active flow

Once through the active flow unit, water enters the main plant’s conventional clarifiers, known as solids contact clarifiers. These units mix incoming water with lime, sodium hydroxide, polymer, and recycled sludge to accelerate clarification.

“The clarifiers give the water a chalky look at first because of the lime,” Smith says. “After settling, the clarified water flows through tubes and into launderers before heading to the filters.”

At this stage, water turbidity is reduced to around 0.5 NTU.

“The river water hardness can be over 500 mg/L, but we bring that down to about 100 to 200 mg/L,” Smith says. “That’s still hard water, but it’s usable.”

The clarifiers are cleaned regularly. Blow-down sludge is pumped to drying beds across the river and alternated every few years for removal.

Ozone and recarbonization follow

After clarification, the water is still too alkaline for filtration, so it’s routed to a recarbonization tank where carbon dioxide is added to lower the pH from over 11 to around 8.

Then, ozone is introduced. The system, installed in 2021, generates ozone onsite using high-purity oxygen and electricity.

“Ozone is one of the most powerful oxidants available,” Smith says. “It disinfects and denatures organics that cause taste and odour.”

The ozone system includes 48 reactors, each with an independent power supply. Heat from the process is cooled using glycol, which also helps heat the plant in winter.

Advanced filtration delivers pristine results

Post-ozonation, water is filtered through biologically active dual-media filters composed of anthracite and sand. Despite the original 1978 filter housings, modern stainless steel underdrains ensure high performance.

“We’re required to reduce turbidity to 0.3 NTU,” Smith says. “But we consistently get it down to 0.1 or lower.”

After filtration, the water enters a small in-plant reservoir used for backwashing and internal systems. It is then pumped to a second set of filters: the granular activated carbon (GAC) contactors.

“These are basically industrial versions of a Brita filter,” Smith says. “They’re great for taste and odour.”

Though GAC filters also remove organic material, Manitoba’s high dissolved organic carbon exhausts the media within six months, making it impractical to replace frequently.

“One filter’s media alone costs over $150,000,” he says.

Final treatments and distribution

In the last stage, fluoride and chlorine are added in a separate chamber. The plant uses gas chlorine and liquid fluoride, which Smith defends despite controversy.

“Calgary removed fluoride and saw a spike in dental caries,” he says. “They’ve just reinstated it because the difference is so dramatic.”

The water then rests in an on-site reservoir for at least an hour — far exceeding the regulated 20-minute contact time for disinfection.

Two lines distribute the treated water. One line supplies the city and includes orthophosphate to reduce corrosion and protect homes with legacy lead service lines.

“Over 300 homes still have lead pipes,” Smith says. “Orthophosphate helps prevent lead from leaching into the water.”

The second line supplies Poplar Bluff Industrial Park, Simplot, WOCAT, and the Yellowhead Regional Water Co-op — reaching communities as far as Austin and Plumas.

Designed for complexity, built for taste

Unlike many treatment plants, Portage la Prairie’s system includes active flow, ozone and GAC filtration — technologies not found in many other municipal setups, including Brandon.

“In today’s dollars, the whole system would cost about $200 million,” Smith says.

Despite being built nearly 50 years ago, the plant is running at near-capacity and managed to exceed its design flow rate of 34 million litres per day once this past June, reaching 36 million.

“Our annual average is about 26 million litres per day,” Smith says. “That makes us the second-largest public water plant in Manitoba by volume.”

Award-winning water

In September, Portage la Prairie won the Best-Tasting Water award at the Western Canada Water conference.

“We beat out mountain communities with pristine sources,” Smith says. “It’s pretty satisfying when you consider we’ve got some of the dirtiest raw water in North America.”

Equipment, expansion and daily testing

From ozone chambers to sand filters and sludge ponds, the plant’s infrastructure has been continuously upgraded. Clarifiers built in 1978 still operate, with blowers and scrapers running under strict maintenance schedules.

The ozone system compresses and purifies air to nearly 97 percent oxygen before using electrical discharge to generate ozone. Glycol-cooled and chiller-supported, the setup is state-of-the-art.

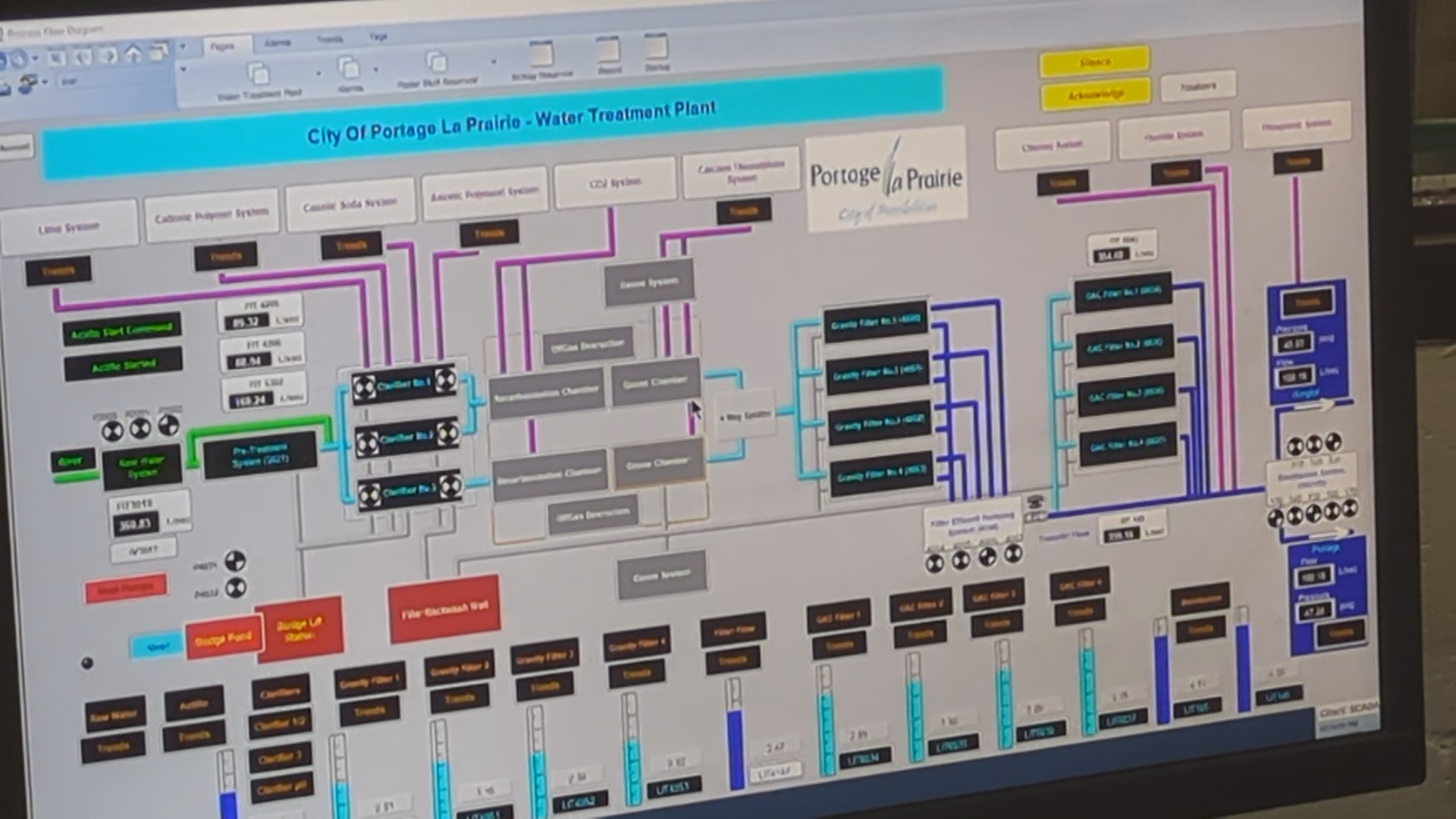

Plant operations are monitored via a SCADA computer system in the control room. Real-time data from across the facility, including reservoirs, slakers and filters, help staff ensure water quality.

Daily lab testing includes turbidity, chlorine, hardness, chloride and alkalinity, all benchmarked against provincial standards.

GAC and future expansion

Upgrades to GAC filters began in 2003, with underdrains designed for optimal performance. Smith leads a tour showing black carbon media tubs where water enters at the top, flows down, and exits polished and ready.

A window in the existing plant wall marks the future expansion site — a walkway into a new addition being constructed east of the main building.

As Portage moves to meet rising demand, its plant remains an example of how sophisticated treatment systems, strategic upgrades and experienced management can turn the murkiest water into a clear victory.