PortageOnline/Photo courtesy of Manitoba Historical Society

A rare military program began with boys' home and parachute drills in Portage la Prairie in the 1940s.

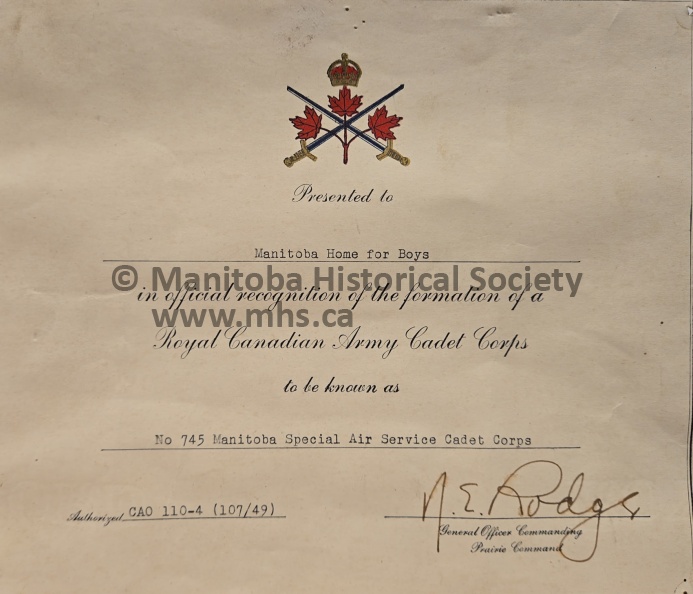

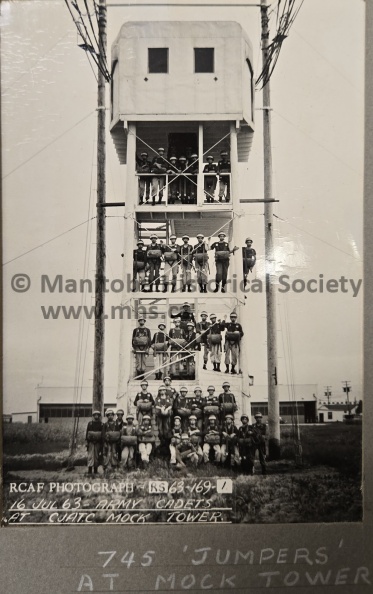

The No. 745 Manitoba Special Air Services Cadet Corps holds a unique place in Canadian military history. Founded on September 25, 1948, it remains the only cadet unit in Canada to have carried the prestigious title “Special Air Services,” modelled after Britain’s elite SAS force.

Though not a combat unit, the Portage la Prairie-based corps was formed with the intent to instill leadership, discipline, and advanced training in youth. Its founders—Lt.-Col. A.H. Gammon, Lt.-Col. E.M. Brown and Major B.D. Jones—secured backing from the Deputy Attorney General and senior military officials in Manitoba. They envisioned a program that would benefit troubled youth and the broader defence community alike.

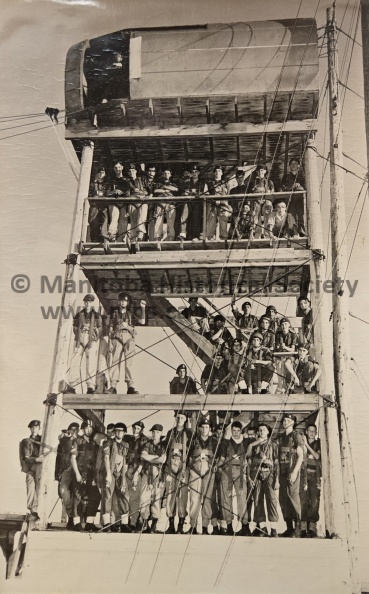

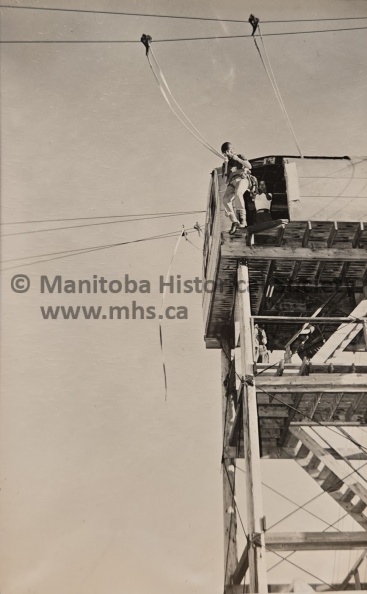

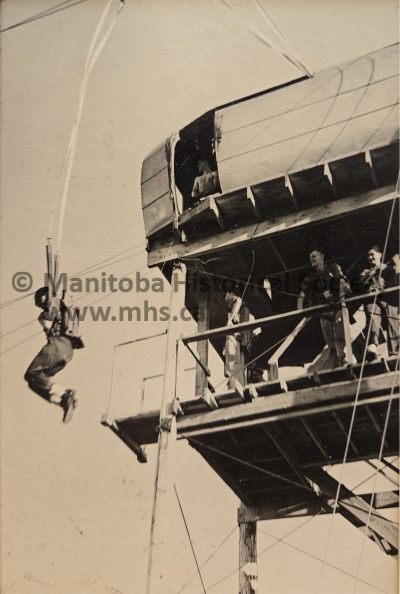

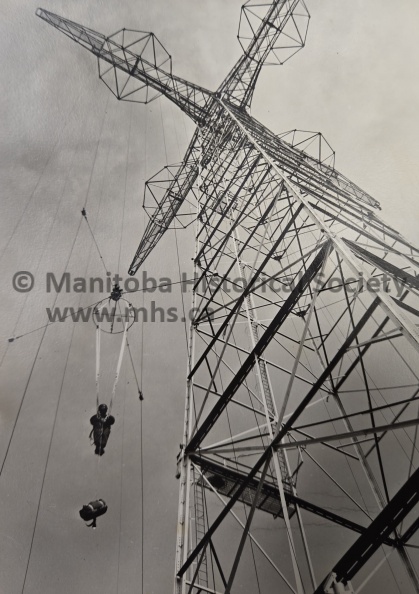

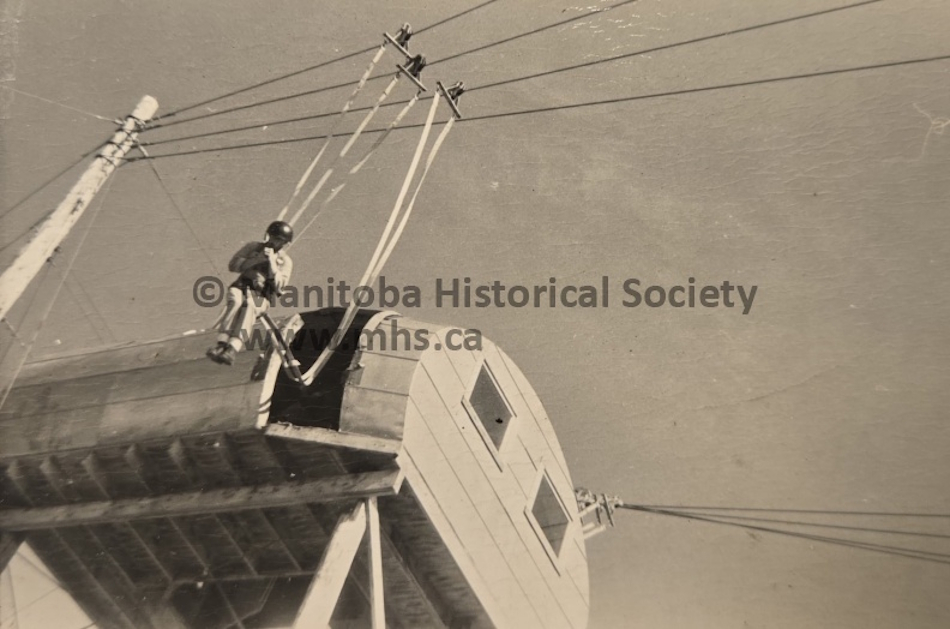

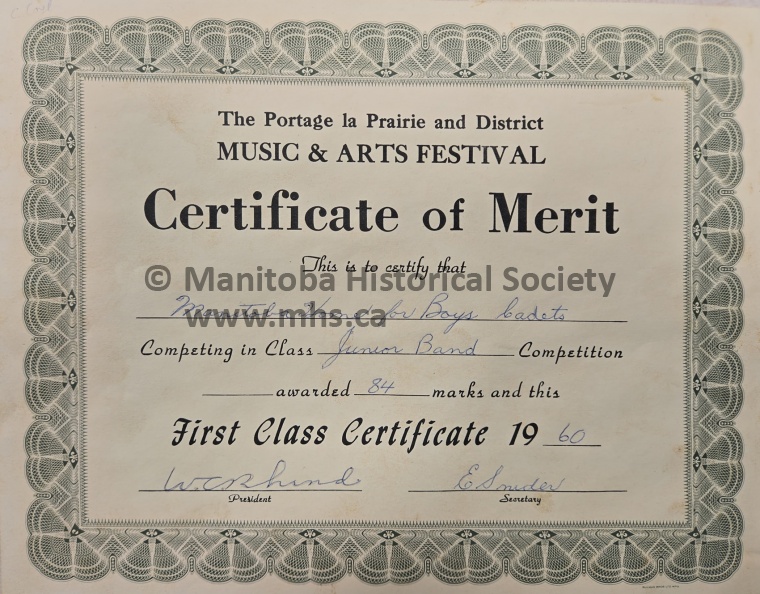

The corps began with a brass band and expanded to include intense summer camps at Clear Lake and then CFB Rivers, where cadets participated in parachute drills using the jump tower at CFB Shilo. These experiences built a reputation for resilience and excellence that surpassed many traditional corps.

Its legacy is now resurfacing through a research project at the South Central Regional Archives.

Summer archivist uncovers forgotten history

Greyson Marchinko, a summer archivist working with the South Central Regional Archives, has been piecing together the story of the SAS Cadet Corps from materials found at the Fort la Reine Museum in Portage la Prairie.

“We found a bunch of photos and documents about the 745 SAS Cadet Corps and what that was,” says Marchinko. “It was the only one in Canada, and it was here in Portage la Prairie. They turned the Manitoba Home for Boys into that cadet corps.”

“It seemed like all the boys who misbehaved and got sent to the boys’ home ended up in that corps,” notes Marchinko.

While the exact parallels with modern army cadet programs are still under study, Marchinko says photos show the boys regularly trained at Camp Rivers and used the jump towers for mock parachute drills.

“There were parachutes, but they were attached to these lines,” adds Marchinko. “They were jumping from these mock towers as a kind of practice parachute jump.”

“They were getting these badges called clipped wings,” he says. “It’s like, you completed the practice, here’s a badge of honour. You’re not actually qualified for parachuting, but you jumped from the scary tower.”

Hundreds of photos and documents uncovered

Marchinko estimates he has uncovered nearly 500 photographs so far, mostly in black and white, ranging from 1949 to roughly 1970.

“I think the first round of photos we found was about 278 and then we found a bunch more,” he says.

In addition to images of training exercises, sports days, and visits to Camp Rivers, Marchinko also discovered official records and correspondence.

“I found a bunch of letters from the people at SAS and the government,” says Marchinko. “It seemed like one of the instructors was trying to get a service decoration after retirement. It was a precedent-setting case.”

Among the more revealing discoveries is a formal document that authorized the conversion of the Manitoba Home for Boys into the cadet corps.

“I have a picture of the document that formalized the formation of the Cadet Corps from the Manitoba Home for Boys,” Marchinko adds. “That was interesting. I was happy to find that because that’s concrete—this is when it started.”

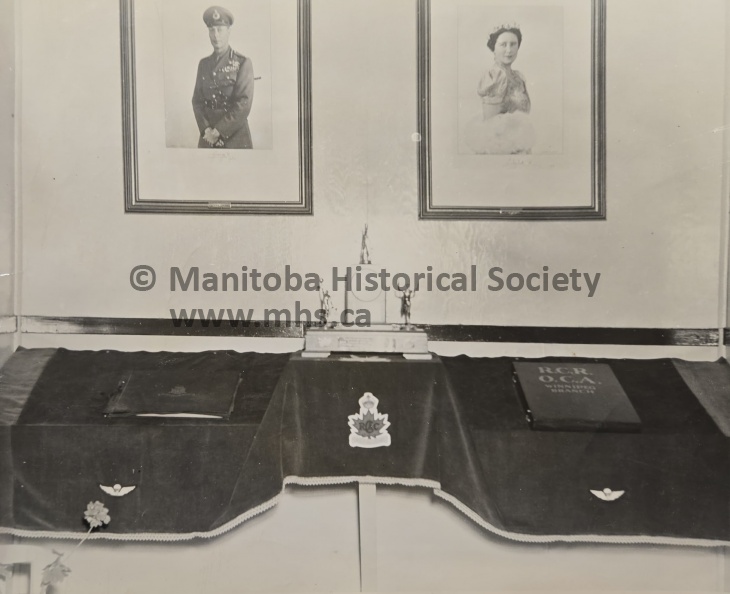

A glimpse into the lives of cadets and instructors

Personal records of cadets and instructors are also part of the collection.

“We got place of birth, languages spoken, religion of all the instructors that ever received a promotion,” says Marchinko. “One of the instructors, Donaldson, he fought in both world wars. He was a cavalry member.”

Though Marchinko hasn’t yet found records explaining how youth were enrolled—whether voluntary or mandated—he has documented cadet names, birthdates, ranks and more.

“It seemed like a lot of people were in and out,” he says. “Some left after a year, others stayed longer. I’m not sure what to make of that yet.”

Scanning and preservation continue

Marchinko is scanning both photos and documents using Adobe’s PDF scanner app, with some negative film requiring a special scanner.

“The photos are the easy part,” he says. “The documents are harder. I have to decide what to scan and what to write down.”

He expects the project to continue for at least another week or two, depending on volume.

“I think just the end of last week we started on those photos, so it’ll probably be six weeks total.”

From cinematic images of cadets marching in front of planes to sports day snapshots and Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Camp Rivers, the project is preserving a one-of-a-kind story of military-inspired youth training in Manitoba.

“This was my first task when I joined here,” Marchinko says. “It’s been a journey.”