Portage la Prairie’s Crescent Lake, a cherished water feature dating back over a century, is undergoing dramatic change. Once created to enhance local recreation and attract wildlife, the Crescent is now threatened by drought, invasive species, and unclear long-term solutions.

Local historian James Kostuchuk, who lives along the Crescent, says the man-made lake has relied on artificial water input since the early 1900s.

“We’ve been pumping water into the Crescent since 1912 — basically around the time of the Titanic,” says Kostuchuk. “Now it’s just shut off, and you could have knocked me over when I heard. I’ve read all the city’s reports since the 1950s on water quality and aquatic life, and I found it astonishing that it all changed in the blink of an eye.”

Kostuchuk says invasive species are a major culprit, and adds that even with the city’s best efforts, a quick solution seems unlikely.

A lake built by design, now drying by default

While the Crescent appears natural, it was originally a constructed water feature. Kostuchuk says much of the land was pasture before the transformation.

“If we don’t get rain, it’s just going to dry up,” he notes. “It will no longer be a kayak route — it’ll be a mud puddle. You won’t be kayaking. You’ll be wearing hip waders just to scramble across.”

Though the changes are alarming, Kostuchuk acknowledges the Crescent has always required intervention to maintain its appeal.

“The decision to create the Crescent was a really good one,” he says. “It makes us special as a Prairie town with a nice body of water, but now it’s threatened — and it’s no one’s fault. There’s just a problem that needs to be fixed.”

A call to reframe expectations

Kostuchuk suggests rethinking the Crescent’s identity as a lake and embracing its natural evolution into something else.

“It’s a marsh,” he says. “Oak Hammock Marsh sees hundreds of thousands of visitors. Bird life is a draw. Some people want to swim or jet ski here, but that’s what Manitoba’s lakes are for. This is a marsh. People need to accept that.”

He adds that calling it “Crescent Marsh” could help reset public expectations.

“They come and say, ‘That’s not a great-looking lake.’ But if you call it Crescent Marsh, suddenly it’s ‘That’s a good-looking marsh.’”

From open water to dry land

Without water inflow, Kostuchuk warns the Crescent could disappear entirely.

“If it evaporates, it’ll just be pasture again,” he says. “We’re not even going to get the marsh. It won’t go anywhere.”

He points to historical records that show the area was once mixed — some parts water, some pasture — before the city expropriated the land.

“In Anne Collier’s book, there’s a man who grew up here in the 1870s who says he took a boat to school from around where the new hospital is,” he adds. “But other reports from that time describe much of the area as pasture.”

City’s ongoing challenge to preserve the Crescent

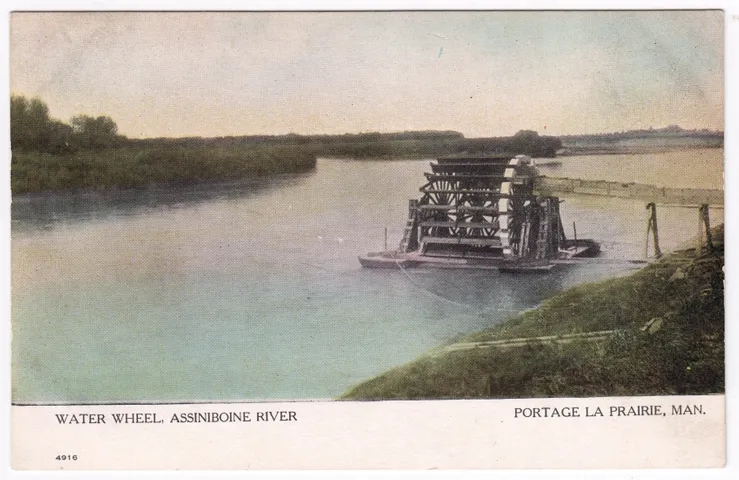

The Crescent’s creation was first proposed by city councillors in the early 1900s to enhance Portage’s natural beauty. By 1912, the city began pumping in water. Since then, upkeep has been a balancing act of ecology, economics, and public use.

Kostuchuk says Island Park wouldn’t be the same without the Crescent.

“It’s a fantastic park,” he notes. “People come from Winnipeg and other places on weekends. The Lions did a brilliant job on the pond. Without the Crescent, it wouldn’t have the same charm.”

He says city council is working with other levels of government, but a long-term solution remains uncertain.

Shifting methods to manage vegetation

Weed control has also evolved. Kostuchuk recalls a time when manual methods were used.

“When I first moved here, they used a weed cutter. The weeds were chopped and used as compost for fields,” he says. “Later, the city switched to chemicals. Even that was expensive — I think around $80,000 a year just for weed control.”

The Crescent’s clear water has made it especially vulnerable to aggressive plant growth.

“The water is very clear, which allows sunlight to penetrate and helps plants grow,” he adds. “It’s so shallow that plants take root easily. That’s great for small fish and salamanders, but not for kayakers.”

A shifting ecosystem over time

Kostuchuk has observed the ecological transformation firsthand.

“When I moved here in the 1990s, after it rained you’d see hundreds of frogs and salamanders on the Crescent,” he says. “Now it’s been 10 or 15 years since I’ve seen that. Last year I didn’t see a single salamander.”

He speculates the decline could be linked to pelican activity or changes in riverbank reinforcement to prevent erosion.

“The biggest change I’ve seen was when they built the Causeway. They lowered the water level for one or two summers. What we’re seeing now is very similar.”

Canada’s largest urban marsh?

Despite the challenges, Kostuchuk sees potential in reimagining the Crescent.

“I couldn’t find anywhere in Canada that claims to have a large urban marsh,” he says. “Maybe Portage could lay claim to it. Given how birds and wildlife are drawn to marshes, maybe that’s an opportunity.”

For now, Kostuchuk says what happens next depends on weather, policy, and public will.

“But there’s no doubt,” he adds, “what we’re seeing is a big shift in what Crescent Lake has been — and what it may become.”